Why We Never Think Alone and Why We Value Publications That Know This – by Dr. Nick Southgate

When people make decisions they do, of course, aim to make the best decision. Our common-sense instinct is that a good decision is well-informed, so people go seeking information.

However, getting to the best decision this way is not only very hard work, it also has a contrary effect: the more effort we put in to a decision the less confident we tend to feel about it.The more we look in to a topic the more we find out. The very knowledge we hoped would inform our decision comes to cloud our decision making.

The cause is simple. The more we know the more we know about small differences. The smaller the difference between two things the harder it is to justify a choice between them. What seemed like a clear difference between, for example, two televisions or two mobile phones vanishes as we find out more.

In fact, what people want to make is a confident decision. As doing this alone is difficult people outsource the decision-making burden: they turn to experts.

Experts do the hard thinking so we don’t have to.

When we turn to experts in any field, from farm equipment to fashion, stock picks to soap operas, we enter in to a community of knowledge. In these communities, the sharing of knowledge allows everyone to know more. Individuals can become specialists if the group remains generalist.

Studying such communities of knowledge has led psychologists Steven Sloman and Philip Fernbach to write a book called The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Never Think Alone.

Their central contention is that we store most of our knowledge outside ourselves, in others, in institutions and even in objects.

However, they are also interested in how this creates a knowledge illusion: we confuse what others know with what we know ourselves.

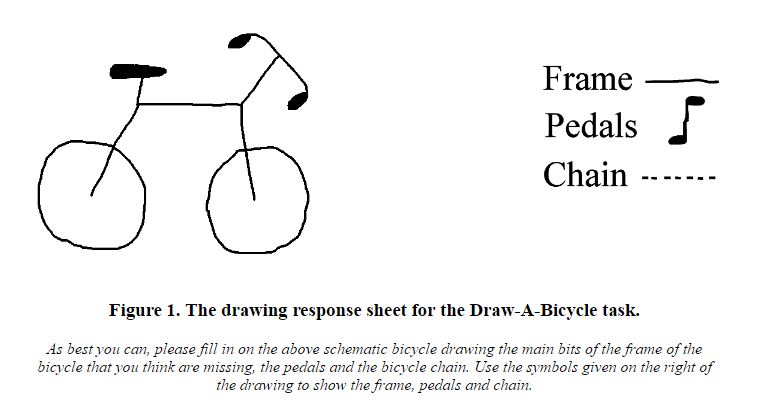

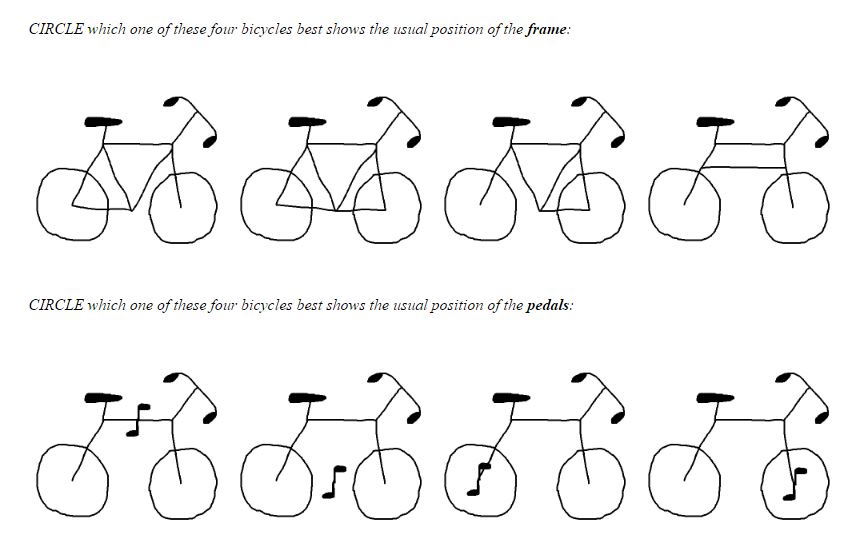

An experiment conducted at Liverpool University asked people to draw a bicycle.

Riding a bicycle is our defining example of a skill you don’t forget. This would imply that people know how a bicycle is put together – how the pedals move, the chain that turns the wheels, how the wheels are held in place by the frame and so on.

In fact, people do very badly at this apparently simple test. This is because we let the bicycle do the remembering for us. Knowing how to use a bicycle is not the same as knowing how it works.

This seems benign enough. However, the effect is more pernicious when we turn to political beliefs. Sloman & Fernback cite a 2012 study that asked Americans if the Supreme Court had overturned The Affordable Care Act (aka ‘Obamacare’). While 36% were in favour of the act and 40% against, only 55% correctly knew that the act was still law. Almost a third of people were willing to express an opinion about a law they didn’t accurately know was law.

Public debate is in a parlous state. In political debate, people belong to communities of knowledge that actively distort and misrepresent issues to the point where people become confused about whether a law is a law.

Escaping the morass of fake news and factional loyalties is a subject for another day.

However, what it shows is how important it is to protect the integrity of the communities of knowledge that we participate in.

This sort of integrity is precisely what strong publications offer (more so than news outlets, although news organisations will contend that writing the first draft of history is a more fraught task than writing a colour supplement).

Nonetheless, people continue to buy and trust magazines that offer expertise on decisions they may only have occasional or one-off interest in, from Bridal Magazines, Health, Diet, Home and Fashion titles. For everyday decisions, every day sources are valuable and trustworthy.

This is the double-edge of The Knowledge Illusion.

One of Sloman’s own studies show how people easily attribute expert knowledge as their own. People are asked how well they understand a new type of rock discovered by geologists.

People who are told that geologists have fully explained the rock rate their own knowledge higher than those told he experts don’t understand it. In effect, we assess our access to knowledge more than our actual knowledge.

However, there is nothing wrong with trusting good science.

Nor is there anything wrong with trusting a reliable source about washing machines or whether the mushroom tuck is on trend.

Editors and advertisers are key stakeholders in making publications reliable communities of knowledge. Honest, interesting, relevant, transparent, exciting and creative advertising surrounded by informed, accurate and equally transparent editorial creates an environment where readers can come to be part of that community.

And when we understand the human need, communities of knowledge meet and we understand that a publication is not merely as valuable as a media space – it is only valuable when we create a trustworthy place where people can come to be part of a healthy community of knowledge.